Just a quick update on the Mississippi kites I blogged about a few weeks ago. Wildcare, after taking in more than 400 of them in the extreme heat, released the last group in a public event yesterday afternoon. My name was one of the first ones drawn to release one of the kites, and I made it into this video news story from the Daily Oklahoman:

http://newsok.com/multimedia/video/1818632656001

The experience of releasing one of the kites that I had volunteered so many hours to feed was gratifying. Rondi and her staff did an amazing job accommodating and caring for all of them, and they released 85% of the kites in time for their annual migration south. Whenever I hear a Mississippi kite’s distinctive “ke-keeeer” in the sky above me, I can’t help wondering if it’s one of the brood I helped feed.

Review: And Hell Followed With It by Bonar Menninger

It should come as no surprise to anyone that books about historic tornadoes often pop up on my Amazon recommendations. I’ve probably read two dozen of them. They’ve ranged from drama-rich to science-poor to saltine-dry, with the occasional pompous self-promotion (usually written by a television celebrity) thrown in for good measure. So when Bonar Menninger’s And Hell Followed With It: Life and Death in a Kansas Tornado (2010), about the 1966 Topeka, Kansas F-5, surfaced in my recommendations, I held off on it for a few months. I finally bought it to read on my recent trip to France. I’m pleased to say it was a solid investment that I thoroughly enjoyed.

I offer the following review with the caveats that (1) I read the Kindle edition, and (2) I have no immediate mechanism for evaluating the accuracy of many of the anecdotes. I assume implicitly (and perhaps naively) that the stories have been recorded and conveyed faithfully. However, the extensive list of references (more than 100 of them) at the end of the book gives me some confidence that the author did his homework.

It’s rare that an author comes along who is capable of weaving together a comprehensive narrative of natural calamity in a manner that doesn’t reduce the victims to near-anonymous disaster fodder (and the scientists studying the event to bookish fools, for that matter). From page one, each person who experienced the tornado is incarnated for the reader – usually via an anecdote not involving the tornado, and more often than not a humorous one. We learn about the fiery Mexican housewife, the Depression survivor caring for his disabled children, the up-and-coming disc jockey, and the 8-year-old boy frantically bicycling to a nearby store to run an errand as the tornado bears down. Details as seemingly mundane as what songs or news stories played on the radio, or what TV programs people planned to watch that night (Lost in Space, anyone?) serve to ferry the reader’s imagination back to 1966. The people described could just as easily have been a reader’s (grand)parents, relatives, friends, or neighbors.

Though the stories jump back and forth in time, Menninger masterfully braids them together to provide context for the disaster while describing the disaster itself. (The book contains a handy index at the end, enabling the reader to cross-reference each person, place, and concept.) We learn the history underlying the Burnett’s Mound myth, and about Richard Garrett’s tireless crusade to leverage the pre-existing Cold War knowledge and infrastructure (read: sirens) to prepare Topeka’s citizens for a tornado that he was sure would come someday. Garrett’s efforts in particular are credited with holding the number of tornado fatalities in his state’s capitol down to just over a dozen, for which he received an Exceptional Service Award from the U.S. Weather Bureau.

There’s also the saga of John P. Finley’s 1880s tornado research, the Weather Bureau’s subsequent ban on the use of the word “tornado” in its products, and the redemption provided by the 1948 Fawbush and Miller tornado forecast. Despite the book jacket’s claim that the above story is “virtually unknown,” it’s old yarn to me. That’s not just because I’m a severe weather researcher, but because that story is inevitably retold in just about every contemporary tornado book I’ve read! But that’s a minor gripe about the promotion, not the writing.

Accounts of the tornado’s destruction – chapter by chapter, block by block – never become repetitive. The stories are still just as compelling, and the dread just as fresh and palpable, in Chapter 15 as in Chapter 1. The last couple of chapters deal with the aftermath on scales ranging from personal to national. We learn the fates of the survivors, some of whom had to deal with the physical and mental trauma, in some form or another, for the rest of their lives. Some even report bits of debris still emerging from their skin 20 years later!

From a meteorologists’ perspective, I could not find much to complain about. The highway overpass myth is firmly dispelled at several different points in the book, including the forward. (Several victims encountered the tornado along I-70.) Menninger does a decent job of articulating the state of severe weather science in 1966, and how newer insights have helped to illuminate the events described. However, many of the meteorologists profiled are now deceased, and I did not have the pleasure of meeting them. Perhaps some of my readers can offer their insights as to the accuracy of their stories.

Lay readers, disaster buffs, and professional meteorologists alike should find something to appreciate in And Hell Followed With It. The author has done a remarkable job of aggregating a colossal amount of information about the Topeka tornado and conveying it in a narrative that is digestible, compelling, and sometimes even funny. And Hell Followed With It should set a standard against which other comprehensive tornado histories can be judged.

Hot topics

After getting off to a comfortable start with slightly above-average rainfall, summer returned with a vengeance to our neck of the woods. Our lawn, once lush with growth, is now mostly brown and crispy underfoot. I cycled home on Thursday evening crossed by a withering, 111 oF southerly wind. Friday, our 16th consecutive day with a maximum temperature greater than 100 oF, saw the introduction of a statewide burn ban as winds gusted to 25 mph. I crossed my fingers that the firefighters would stay bored, but unfortunately a smoke plume appeared southeast of the NWC around lunchtime.

As evening fell, we saw an orange glow on the eastern horizon, like a false dawn, as we walked our dog around the block. We had “grab and go” bags packed just in case the fire decided to get ornery. Fortunately, it remained well east of our neighborhood. However, several of our friends living farther east, along the south shore of Lake Thunderbird, did have to evacuate for a time. The overnight diligence of firefighters kept the flames off their doorsteps. Other people living farther east were not as lucky.

An even bigger fire erupted northeast of Oklahoma City and destroyed significant swathes of Luther, OK. The outrage over the apparent act of arson that started this fire made national headlines. And the danger’s not over – Another week of 100+ oF high temps is on tap, but not a drop of rain in the offing.

I grew up in Minnesota, where we have a certain machismo about winter: bragging about how low the wind chill was while we waited for the bus, how tall the snow drifts at the end of the driveway got, etc. Winter is a fact of life, and we’ve learned to live with it, even celebrate it. I’ve lived in Oklahoma for 10 years now, and found the exact same to be true of Oklahomans and the oven outside. Heck, I’ve even come around to join then. (“Whoa, you cycled when it was how hot?”) Nonetheless, I’m looking forward to the more temperate days of fall. Believe me, they can’t come soon enough!

New pub

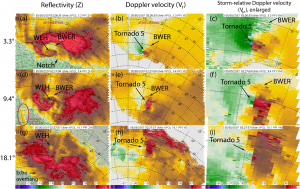

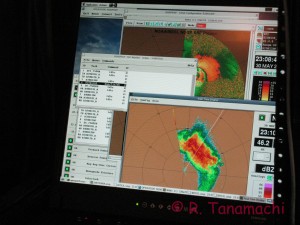

I’ve got a paper in this month’s Monthly Weather Review entitled Mobile, X-band, Polarimetric Doppler Radar Observations of the 4 May 2007 Greensburg, Kansas, Tornadic Supercell. This is the first of two planned papers based on my Ph.D. research, an observational study based on UMass X-Pol data that we collected in the Greensburg storm.

A local sheriff showed us to his favorite storm spotting place on a hill looking over Protection. That road was too muddy for us to use, so we moved about two miles east and deployed on a packed gravel road. As we lost daylight fast, the storm dropped a rotating wall cloud, followed by a brief tornado and an additional funnel cloud to our west. We got volumetric, polarimetric X-band data of all these features. At one point I had to back the truck up to avoid beam blockage from telephone poles along US Hwy. 160, resulting in a small gap in the data.

En route back to Norman around midnight, congratulating ourselves on a great first deployment of the season, my cell phone rang. Chip L. had been chasing with us earlier in the afternoon, but split off after our tire mishap. “Greensburg has been completely destroyed,” he said solemnly. As an EMT, he had gone there to assist, and witnessed near-complete devastation of a town of ~1500. We stopped at a fast food restaurant in Ada, where a TV screen in the corner of the room flickered images that looked like they’d come from a war zone. The remainder of the drive back was much quieter and more somber.

In the years since that night, I’ve driven through Greensburg several times, and have been continually amazed by the community’s resilience and resurgence. When the time came, I dedicated my dissertation research to all the victims of the Greensburg tornado. Although improved scientific understanding can never undo the pain to the Greensburg community, I’d like to think that this study was one small, positive thing that came of an otherwise wholly devastating event.

No Time Toulouse

At the Météo France conference center, I presented a talk (about GBVTD analysis of W-band data we collected during VORTEX2) and two posters (both on EnKF assimilation of mobile radar data in supercells). I reconnected with domestic and international colleagues, as well as making some new acquaintances. Between sessions, we had receptions and banquets at several Toulouse landmarks, including City Hall and the 800-year-old Hotel Dieu.

I figured out early in my stay that I couldn’t possibly pack in all the activities I wanted to do in one week. It’s just as well, because I kept getting lost! And of all the cities I’ve visited, Toulouse was by far the best city to get lost in, slow down, and enjoy.

I’ve returned to find summer baking Oklahoma in earnest. It may not be too long before we dust off the dust devil chasing gear again!

2012-05-30: Paducah, TX landspout

On 30 May 2012, I had the honor of tagging along with the NOXP radar (with my husband Dan D. and Ted M. as crew), operating in support in of the Deep Convective Clouds and Chemistry Experiment DC3). Although the morning’s SPC outlook highlighted a SW KS-NW OK corridor for severe thunderstorms, some of the high-res models indicated that there would be an earlier outbreak of storms along the dryline in the E TX PH, in response to a developing cyclone and robust moisture return. Any cold pools laid down by the storms in Texas had the potential to muck up the Oklahoma target.

Farther west, storms fired off the dryline and promptly split. Right-movers tracked southeast, prompting the DC3 radars (SR1, SR2, and NOXP, led by Dr. Mike Biggerstaff) to head south out of Altus on U.S. Hwy. 283. A few participants grumbled about the choice to head south rather than take more direct route west. However, the objectives of DC3 are a bit different than in VORTEX2. Priority number one is long-duration, dual-doppler data in convective storms, so the radars set up well in advance and collect as the storms pass by. (Tornadoes are not the main focus of DC3, but they’re considered a nice bonus.)

After crossing the Texas border, thereby committing ourselves to chasing right movers, Dr. Biggerstaff decided to target the southernmost storm in the cluster, which was headed for Paducah, TX, and set up his dual-Doppler lobe on U.S. Hwy. 70 between Crowell and Paducah. As the crew NOXP’s scout vehicle (a mobile mesonet called Scout 3) drove ahead to locate a suitable deployment site and hold it for the radar truck, a few dramatic dust clouds arose on the updraft-downdraft interface, some with gustnadoes and shallow rotation. One dust tube (pictured at top) extended up hundreds of feet, almost touching cloud base. It was unclear whether it as connected to the nearby mesocyclone or shear-induced, so I’ve been calling it a “landspout” in my discussions.

We undeployed and headed south again to U.S. Hwy. 82, where we learned that the DC3 balloon crews had stopped operating. NOXP headed back north again for a second deployment on U.S. Hwy. 83, targeting a second supercell following much the same track as the first Paducah supercell. Although the storm had a nice inflow tail, it appeared to be outflow-dominated, with a rolling dust cloud spilling out in front of it.

During our hasty, hail-induced departure from Paducah earlier in the afternoon, we had had to leave behind a pair of NOXP’s metal plates (placed underneath the hydraulic levelers on soft soil). As we returned to the site to retrieve the plates, we observed sporadic wind damage throughout Paducah. Garage doors had buckled inward, roof shingles and small brances were strewn across lawns, and the power in Paducah was out. A few miles east of Paducah, near the intersection of U.S. Hwy. 70 and County Rd. 301, we encountered a metal outbuilding that had been about 50% demolished by a particularly intense wind swath. Sheet metal had been peeled off and scattered to the southwest of the structure, wrapped around telephone poles and road signs up to 1/4 mile away. (I couldn’t get any photos owing to darkness.) Curiously, a second metal building across the street, a few hundred feet to the south, appeared untouched. Some very localized wind phenomenon (small tornado? microburst?) had inflicted substantial damage there.

After retrieving the plates, we made our way back to Norman by way of Childress, TX. Now in the driver’s seat, Dan fought a 70 mph head wind in Lawton, pushed out by collapsing storms dozens of miles to the north. We pulled back into the NWC around 2 a.m.

Partial solar eclipse as seen from Norman.

This was the view from the roof of the NWC at about 8:16 p.m., before the sun dipped behind a very inconsiderate cumulus cloud kicked out by a pulse storm near Watonga.

It’s events like this that make me wish I were a better photographer!

A storm chaser’s review of the Bloggie 3D pocketcam

Here’s an example of 3D video I shot on our approach to Cherokee, OK on 14 April. YouTube was smart enough to recognize the H.264 3D format.

Pros:

It’s teeny, about the size of a smart phone. It’s also fairly intuitive to use, with minimal buttons and menus. I was able to explore most of the functionality before I ever had to crack open the manual. (Owing to the small box size, the camera only comes with a “quick start” instruction card; the full manual is available on Sony’s web site.)

There’s no need to use the pre-loaded “Bloggie” software (intended to facilitate quick sharing of video via Facebook, Youtube, etc.) to offload the videos in Windows 7; the “import” function works just fine. Like other pocket cams, it interfaces with a computer via a Swiss-army-style USB 2.0 port. The viewfinder is actually a “Magic Eye” 3D display, which I find nifty. The camcorder also interfaced cleanly with our 3D-capable Samsung HD TV using a mini-HDMI cable.

The 1080 HD video and audio quality are surprisingly good. I used it on my 14 April chase as a dash cam, turning it on and off whenever something interesting came into view. The battery held out through the entire chase (although admittedly, I was rather frugal with it). My highlights reel from 14 April 2012 contains video from both the Bloggie (dash-cam shots) and my Canon Vixia HV30 (handheld and tripoded). Can you tell the difference?

Cons:

The internal media only holds about 80 minutes of 1080 HD or 3D HD video. I would love to be able to expand to an SD card, but unfortunately this model does not have that option.

The Bloggie isn’t weatherproof, so you have to keep it dry. Sony makes another model called the Bloggie Sport, which is waterproof, dirt-proof, and drop-proof, but it doesn’t shoot 3D. Oh well.

At the moment, my current video editing software of choice, Adobe Premiere Elements 10, doesn’t support stereoscopic 3D editing. That’s why I had to upload my first tornado clip sans editing or copyright overlays. Adobe Premiere Pro supports 3D, but of course it is considerably more expensive. I can only hope 3D editing is on the horizon for Premiere Elements 11.

To summarize, the Sony Bloggie MHS-FS3 is a relatively cheap (<$200) gateway to 3D HD video. It could benefit from some weatherproofing, a few more user control features (particularly the focus), and affordable video editing software. However, it's something new, lightweight, and fun in my chase gear bag, and I look forward to testing it out on future storms.

2012-04-30: LP supercell near Claude, TX

The last week of April saw the arrival of this year’s Windom High School group from southwest Minnesota, consisting of nine enthusiastic, weather-savvy seniors, their teacher, Craig Wolter, and three chaperones. Each year, Craig takes his top ten or so students on a five-day storm chasing trip to Norman, where the students get to visit the NWC and meet and greet with meteorologists there. Craig has a tight itinerary for his students upon arriving in Norman, but it can always be pre-empted by a decent chase setup. As a fellow Minnesotan, I have a soft spot for Craig’s kids, and always try to lead them on at least one chase. If there had been such a program at my high school, I would have killed to get on the trip!

The Claude, TX supercell eventually became outflow-dominant, so we decided to re-target the next storm to the east (the Hedley, TX storm), whose birth we had witnessed about an hour before. We retraced our route southeast on U.S. Hwy. 287, then went east on TX-203. We thought we would be able to core-punch the Hedley storm without too much trouble as it lifted northeast, then emerge from its forward flank and with a view of the hook to our southwest. However, radar updates showed new storm cells erupting to the south of, then being ingested by, the Hedley storm. These processes interfered with storm consolidation and hook formation, and also resulted in our spending more time in the hail core than we expected, our vehicles pelted with nickels and dimes for nearly 40 minutes.

We took a rather circuitous route back to Norman via Lawton, attempting to avoid a southward-diving hailer over Hobart, OK. We returned to Norman around 1 a.m.

In the days since this chase, I’ve read an April 30 chase account from Bill Reid, whose Tempest Tour group (including Brian Morganti) was much closer to the ambiguous lowering than we were. Even with his close proximity, he wasn’t certain what to call the feature, and after viewing his video, I can see why. However, he eventually concluded that this dusty spin-up was indeed a tornado. Bill’s a veteran chaser, and if he says it was a tornado, then that’s good enough for me. Based on his account, I was able to report to Craig that his students were no longer tornado virgins!

Update, 2012-05-07: After looking at video from the Tempest Tours group, the NWS office in Amarillo declared our “scud finger” an EF-0 tornado. So, now, it’s officially official!

2012-04-27: Brief tornado near Council Grove, KS

The cold rain and pea-sized hail began to fall in earnest, driving us back into our cars. We may have glimpsed another funnel on the horizon, but lost it in the rain after a few seconds. To our north was a road hole, forcing us to head east on U.S. Hwy. 56. The remainder of our chase consisted of an attempt to catch another storm to the east of our original target. Unfortunately, it was ingesting stable air, the warm sector long since squeezed out of existence, and we decided to abandon the chase near Osage City, KS. We had dinner at Emporia, then began the long haul back to Norman.

As I’ve gotten older, I’ve gotten little more choosy about which days I chase. (I chalk part of this change up to accumulated experience, and part to having a full-time job and family to support now that I’m done with school.) However, when I have guests along, I’m more likely to bite on riskier setups with more potential failure modes. Even though it required a 5-hour drive each way, seeing one tornado is definitely better than seeing none!