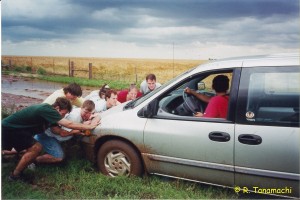

Much has been written over the last week about different storm chaser types. Of course, there are as many reasons for storm chasing as there are storm chasers, so trying to categorize them is tricky business. Distinctions like “amateur” and “professional” – often cited by the media in their coverage – don’t make much sense and can vary daily. I wanted to offer up a metaphor that I find useful when I try to explain the myriad reasons for chasing to non-chasers.

National parks are public, and open to all (as long as you pay the entrance fee!). Storm chasing occurs at the intersections of two inherently public things: weather and roadways. Therefore, anyone who holds a valid driver’s license is potentially a storm chaser. Some people go out with no intention of storm chasing, but are drawn into the hobby in the moment. To me, proposing to legislate or license storm chasing is about as nonsensical as restricting Yellowstone to only geographers and biologists.

National parks can be dangerous. Yellowstone in particular has a diverse collection of hazards – scalding hot springs, bears, bison, steep cliffs, avalanches, rapids, etc. (Incidentally, the book Death in Yellowstone offers a fascinating, if morbid, glimpse at those who have perished within the park’s borders, and how they met their ends.) A thunderstorm, too, can imperil the lives of whose who venture within its domain, deserving or not. People can choose whether to educate themselves about the hazards they will encounter in an effort to minimize their risk. As we saw a week ago, however, Mother Nature always gets the last word, and any sense of control that we have over the situation is illusory. Even the most experienced take their lives into their own hands in an encounter with a storm, or a bear. (There’s a reason we call the area beneath the meso “the bear’s cage“!)

It’s not a perfect analog, but it goes a long way towards explaining to non-storm chasers the complexities inherent in trying to categorize storm chasers. Some are there for the storm, some are there for themselves, and others chase for a spectrum of reasons in between. The only thing we have in common is that we are there because the storm is there. Storm chasing is, was, and will continue to be, what we make it.