Having fallen woefully behind on my chase logs, let me briefly summarize this month’s action so far with a bunch of mini-logs. Many of the longer-range excursions were made possible by a very patient babysitter. Thanks, Miss Autumn!

05-06-2015: Lahoma – Chisholm – Wakita, OK storm Chase partners: Dan D., Jeff S. Nick B., Hamish R.

We headed up toward a prospective S KS target initially, but stopped near Lamont, OK when we heard about a tornadic storm brewing near Chickasha. Not wanting to be suckered into dropping all the way back south, we held up in Pond Creek, watching nascent storms organize. From there, we zigzagged southwest to intercept a beautifully-sculpted supercell near Lahoma that teased us with a few condensation filaments.

Nick believes at least one of them connected with the ground.

@NWSNorman @SRHelicity @tornatrix @Meteodan Funnel with dust tube. Near Carrier, OK, to the west of Enid at 5:15pm pic.twitter.com/NO7HYgD3A9

— Nick Biermann (@plainsnomad) May 7, 2015

From there, we basically reversed our zigzag as we paced the ex-Lahoma storm back toward the northeast, passing through Chisholm, Lamont, and Pond Creek. Meanwhile, we each had an eye on a robust supercell bearing down on Norman, fielding calls from our babysitter about where she and our son should shelter in the worst case scenario. The storm eventually spawned an EF2 that affected the west side of town, and dropped some one-inch hail at our house. Back up north, we finally called the chase off near South Haven, KS. We returned back to Norman close to midnight, witnessing a pocket of damage near 51st street in South OKC on the way, evident from the power outages.

05-08-2015: Norman hailstorm Chase partners: D3

This wasn’t really a chase, but an in situ sampling of severe weather nonetheless. While Dan D. was off chasing near Wichita Falls, I agreed to operate KOUN in the evening. At 5 p.m., I had to leave the KOUN building to collect my son from day care. I was aware of an anemic-looking cell brewing over Blanchard, as well as a larger complex of storms to the west. With no real-time display available, I pointed the KOUN sector to the west and set it a bit wider than usual, then left the site. As I made the drive to day care and back, the sky first grew dark, then green. Simulcast TV coverage on the radio informed me that the situation in west Norman had deteriorated quickly. My son chattered excitedly from the back seat, “Storm there?” Then, as I passed the hallowed ground of 1313 Halley Circle, the hail and driving rain began to fall in earnest. I had planned to grab my son and dart into the building as quickly as I could, but as soon as I opened my car door, I was blasted in the face with one-inch-diameter hailstones and blinding rain.

Blinding rain at the ROC, with occasional 0.5" hailstones #okwx pic.twitter.com/u9zcVjA7xN

— Robin Tanamachi (@tornatrix) May 8, 2015

The Blanchard storm had indeed intensified and generated both a hook echo, and a swath of 2.5″ hail near Tecumseh & I-35 (about a mile to my north). Once the icy battering subsided, my son and I went inside together, where I found KOUN merrily collecting data in the sector I’d left it on. I hope it captured the rapid intensification. (I offloaded the time series to someone else who will process it later this season.) After about 6:30 p.m., with the Norman storm now well off to the east and an antsy toddler trying to climb out of his playpen, I decided to call it a night, and returned control of KOUN to the ROC. Naturally, as we were driving home, the ex-Norman storm reintensified and produced a tornado near Shawnee. Garbage! KOUN was still collecting in VCP 11, so it captured this event, just not in the rapid-scan mode I’d been using earlier.

05-09-2015: Near-miss at Burkburnett, TX Chase partners: Dan D., Jeff S., Nick B., Steve W.

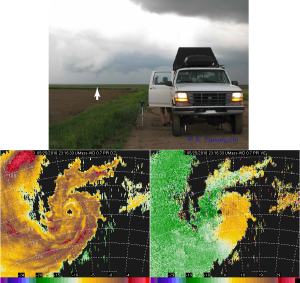

Our initial target on this day was Wichita Falls, TX. A supercell had already gone up near Abeliene and was happily producing tornadoes, but it was too far south to be a viable target for us. We contemplated targeting two developing storms: one near Jacksboro, TX, and one nearer our latitude, approaching Electra, TX. We opted to take a look at the Electra storm, leaving the option open to drop south to Jacksboro. We moved a couple miles north of U.S. Hwy. 287 on Harmony Rd., and took in the Electra storm as it surged forward to swallow us into its navy blue maw.

05-16-2015: Elmer-Tipton, OK tornado Chase partners: Dan D., Jeff S. Steve W., Mark S., Mike C.

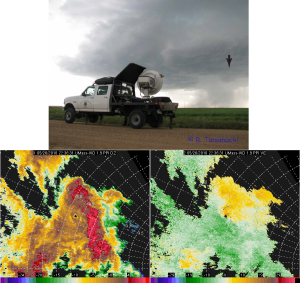

After considering targets ranging from Shamrock to Childress, we decided on the latter, and headed southwest in a three-car caravan. As we drove first down I-44, then west on U.S. Hwy. 62 from Lawton, storms near the northern end of our target range quickly congealed and squalled out. We watched Spotternet icons bail south on U.S. Hwy. 83, converging on the Childress, TX area, where a storm near the southern end of our target was showing promising signs of rotation. The fields around Altus were shiny with standing water, and we were justifiably concerned about going off pavement. We headed south from Gould to Eldorado, where we decided to attempt an intercept on the ex-Childress storm, now crossing the Red River. Rather than heading northeast on OK-6, we chanced E1750 Road because it was marked as “paved” on Roads of Oklahoma. (It was, for all but one mile.) We paused briefly at a service station near Elmer, OK, to watch the storm approach from our southwest, encountering numerous other chasers at the intersection with U.S. Hwy. 283. With no east option out of Elmer, we hedged north and then east on OK-5.

We stopped on N2080 Rd and watched the supercell approach. Tornado warnings began to blare from our weather radio, but all we could see beneath the “wedding cake” and beaver tail was murk.

Then, suddenly, there it was, emerging from the rain like a wraith:

I stood behind our Prius V., attempting to tripod my camcorder. I was so mesmerized by the sight that I failed to perceive the giant hail cratering the ground around me. (White streaks can be seen in the photo above.) A baseball exploded on the ground by my feet, and my husband’s frantic admonitions finally registered. I ducked under the open hatch, taking my camcorder with me. I couldn’t risk running around to the driver’s side door, so I simply climbed into the boot of our Prius V and pulled the hatch closed behind me. From there, it was an awkward crawl over Steve W. in the back seat, up to the driver’s seat. In my haste, I left the camcorder back in the boot, so unfortunately my video ended there. I contented myself with sending a tweet or two from my seat. My husband, however, managed to get some nice shots, which can be seen in this summary:

When the tornado was about 3/4 mi away, we decided to reposition a few miles east. Our car stopped 2 mi W of Tipton, while Jeff S. and Mark S. stopped about 1.5 mi W of us, near the North Fork Red River bridge. They were actually much closer to the tornado as it cross OK-5; Jeff S. claimed he could hear the “waterfall” sound as the white cone passed them:

From our vantage point, I’m fairly certain that we witnessed the formation of a brief, second funnel to the northeast of the primary tornado.

New tornado NW of Tipton. Looking NW from 2 mi W of Tipton. Old tornado now crossing Ok-5. pic.twitter.com/N8PavW4Lxv

— Robin Tanamachi (@tornatrix) May 16, 2015

From Tipton, we followed the hordes east on OK-5C to Manitou, then north on U.S. Hwy. 183, then east on U.S. Hwy. 62 again. Every time I glanced back over my shoulder at the hook area of the supercell, all I saw was a rotund, turquoise curtain of rain. According to the surveyed track above, however, the tornado continued to hypotenuse ENE from Tipton to Snyder, OK, where it finally dissipated.

Our group determined that it would probably be better to drop south to the next storm in the line, which was headed for Grandfield, TX. From Indiahoma, we dropped south to Chattanooga, watched an intermediate storm gust out from near the intersection of OK-36 and OK-5, then finally made a last stand at Randlett before calling it a night. On our way back via Duncan, we heard reports of a new tornado near Geronimo, generated by the ex-Elmer storm.

05-23-2015: Mini-supercell bust near Alex, OK, flooding in Purcell Chase partners: Dan D., D3

We had basically blown off Saturday’s chase prospects because it looked like the primary target (vicinity of Lubbock, TX) was too far away. We were quite astonished later when Jeff S. called us to report a large tornado in progress near Minco, as seen on television. As we switched on our TV, another touched down near Newcastle, just west of Norman. Mini-supercells (a.k.a. low-topped supercells) were developing all across south central Oklahoma in advance of an approaching MCS. We jumped in our car and intercepted a couple of these diminutive supercells down the line, one near Blanchard, and another near Alex, OK, only to watch them shrivel as they were undercut by the gust front surging out ahead of the slow-moving MCS. D3 was a very good sport, watching the rain and lightning from his car seat. We didn’t want to stray too far from home on his account, so we stuck a fork in our chase a little earlier than usual and headed back to Norman via OK-39. The route took us through Purcell, where we encountered some pretty serious street flooding. I was afraid our Prius V might stall out; in some places the water as as deep as 8 inches. We trailed some taller vehicles to gauge the water depth, and made it back to I-35 without incident.

As the evening progressed, the MCS all but stalled out over over us, dropping 6″ of rain at our house. We heard of flooding all over Norman, particularly in East Norman close to Lake Thunderbird. One of our favorite local restaurants, Clear Bay Cafe, posted on FB that they were closed due to flooding. They are only open during the summer, and I imagine this is a season-ender for them. Some of our friends also found water intruding into their homes overnight. Our house is located partway up a hillside, so we had no issues at our house. However, the land just to our east was recently graded for construction of a new subdivision, and tons of bare soil washed downhill, filled our streets with red mud, and narrowed Dave Blue Creek. In the image below, you can see some of the construction equipment in the background.

Erosion in action! Dave Blue Creek clogged with topsoil washed down from land graded recently for a new subdivision. pic.twitter.com/FLXVsrloy5

— Robin Tanamachi (@tornatrix) May 24, 2015